Population & Demographics 1940 – 1960

1940:

Colbert: 34,003 total population

Lauderdale: 46,230 total population

(See Census records)

1960:

Colbert: 46.506 total population

Lauderdale: 61,622 total population

In 1960, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) estimated that Lauderdale County had 7,267 black residents out of 61,622 – representing 11.8% of the total population. In the same year, Colbert County had 8,982 black residents out of a total 46,506, representing 19.3%. Within that county data: Florence had 4,893 black residents of the 31,649 total (15.5%); Sheffield had 2441 out of a total 13,491 (18.1%)

General Summary

There exists a pervasive myth that the Shoals area was distinct within the state of Alabama during the years of the civil rights struggle from 1945-1975, representing what historian Frye Gaillard called an “oasis of cooperation.” In some ways, this assessment is accurate. It is clear in the historical record that the Shoals had relatively few incidents of racial unrest and white supremacist violence compared with the rest of the state and that integration seems to have come somewhat voluntarily and mostly peacefully And yet, while this general impression may seek to buttress local boosterism and assuage consciences, it obscures a more complex reality. The Shoals, quite simply, did not experience the revolution of the twentieth century black freedom struggle in the same way that other regions of the state did. For one thing, as the demographic data show, the Shoals’ population differences were connected to centuries long patterns of settlement based on economic production, including the forced movement of enslaved laborers to the region before the Civil War.

After the Civil War, the Shoals economy was not monopolistically agricultural, and much of production depended on northern companies and the presence of the federal government, particularly TVA, which had consequences for racial attitudes. This meant that the Shoals community stood to lose significant federal money and economic investment by resisting racial integration, while the demographic realities meant that civil rights demands would not change the fundamental racial power structure. Black freedom movements and efforts in the Shoals were largely interpersonal—facilitated through interpersonal relationships, individual legal battles, and biracial committees. They succeeded, often, in procuring desired outcomes, but this individual cooperation as well as the proportional populations, forestalled many large-scale demonstrations as occurred elsewhere in the state. In conclusion, the Shoals did not experience the violence and unrest found in other parts of the state, but, rather than interpreting that as the result of a community commitment to racial justice, it seems more the result demographic realities, the absence of national civil rights groups, the disproportionate presence of white northerners/racial liberals in the business community, and the presence of the federal government/federal financial dependence. Fewer instances of conflict may have actually obscured the realities of racial inequality in the Shoals and allowed insidious forms of white supremacy to flourish, unchecked underneath the mythology of progress.

Economic Summary

The economic development of the Shoals reflects an important distinction with the rest of the state. Prior to the Civil War, agricultural production constituted a significant aspect of the economy. In 1860, for example, the enslaved population of Lauderdale County was 6,737, while Franklin County (now Colbert County) listed 8,495 enslaved laborers. [Please see the American Panorama project for the movement of slavery into North Alabama] During the twentieth century, though, the economy of the Shoals shifted more towards industry, specifically with development of the Tennessee Valley Authority. The TVA brought jobs, capital, and a federal presence to the Shoals, making the area unusually compliant with federal rulings and dependent on federal funding. It also brought large numbers of non-Southerners to the region to work. Additionally, the TVA employed large numbers of black workers, even utilizing racial quotas to ensure some parity in hiring.

Despite this, racial discrimination was not uncommon. Black workers were assigned to more menial, unskilled jobs, and, accordingly, paid less. (The pay scale for example at Wheeler Dam was approximately 45 cents for unskilled labor compared with $1.00 for skilled labor). Racial discrimination extended to TVA projects, namely dislocation, as African American farmers (about 11%) were more frequently affected by damming.

Direct Action & Voting

Unlike Montgomery, Birmingham, or Selma, national touchstones for black grassroots activism, the Shoals did not have large-scale direct-action protests in the 1950s and 1960s.

While local ministers, educators, and civic leaders pressed for equality in the Shoals, a fulsome movement as emerged in other places—boycotts, sit-ins, kneel-ins, marches—seems largely absent. One exception was when Charlies Brown, a black man, sat at the whites-only lunch counter of Spalding Drug Co. in downtown Florence. On November 2, 1961, Brown, a regular customer, sat at the counter to order lunch for a white co-worker. When asked to leave, Brown refused. But no large altercation seems to have followed. The police arrived and Brown was taken into custody, but he claimed he had no activist intent and was soon released with only a fine for ‘breach of peace.’ (“Negro Pays Fine After Entering Plea Early Today,” Florence Times, November 3, 1961) Nonetheless, it was reported, worriedly, as a “possible local sit-in attempt.”

Voting was another important facet of direct action. SNCC’s Voter Education Project issued a report regarding voting efforts from April 1963-March 1964, claiming that, despite difficult literacy tests (with questions that changed every month, as voter education projects were preparing black applicants), poll taxes, and the requirement of a registered sponsor, “Registration by Negroes is not too difficult in the TVA area such as Huntsville, Tuscumbia, Decatur and Florence.” The Voter Education Report also noted that it was planning a large rural effort for the summer and fall of 1964 and would include the “the TVA area.”

A SNCC Report bears this out somewhat:

Colbert: 4575 voting age blacks, 1300 registered, 28.4%: 7.1 %; Lauderdale: 3726 voting age blacks, 900 registered, 24.2%: ONLY 4.6% of total.

In the state in 1965 only 19% of black voters were registered compared with 69% of whites.

Florence was listed by SNCC in 1963 as one of three places in Alabama where “Some progress toward integration has occurred,” (page 18) along with Anniston and Huntsville.

The aforementioned Colbert County Voters League was founded in 1943 by William Mansel Long, an employee of the Tennessee Valley Authority, to promote black voter education and voter registration. It had largely fallen inactive until 1956 when it housed NAACP initiatives. From 1956-1965, the Voters League requested that blacks be able to serve as election holders at polls, as election officials, and to serve as policemen and firemen. These efforts, typically conducted via official petitions to municipal leaders, proved successful in many cases. In 1964, two black men were hired onto the police force. [Please see the Florence-Lauderdale Public Library Oral History with Clifford Crenshaw] The Florence City Board of Commissioners created a biracial committee in 1964, made up of Roy Stevens, Rev. Butler, James Ayers (white), and Dr. Hicks, Rev. Nelson, and P.L. Thomas (black).

The Shoals, or Tri-Cities, did have an active NAACP chapter. First chartered in 1923 by Mary Hough in response to the racist treatment of black WWI veterans, including her brother, the chapter organized the community until 1956, when the NAACP was outlawed by the state of Alabama. From 1956 until 1965, when the NAACP chapter was re-established, black activists, under the leadership of Huston Cobb, met under the auspices of the Colbert County Voters League, among others. [Please see the Florence-Lauderdale Public Library Oral History with Huston Cobb] Since 1965, the NAACP has addressed racial issues in education, voting, and law enforcement.

Education

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation in schools was “inherently unequal,” overturning the Plessy precedent and setting the stage for the eventual integration of schools throughout the American South. In huge font the Florence Times declared the stunning news: “Supreme Court Bans School Segregation.”

School segregation in Lauderdale County and the Florence Schools meant inequality for black students. While white students learned in stately buildings, black students were mostly relegated to local churches or privately funded facilities. Black students received less than half the funding as their white counterparts for books and other educational supplies. With Brown, the Court mandated change under the Constitution.

But that change would take a while. Ten years after the initial decision, in 1964, the Florence City and Lauderdale County schools (Superintendent Allen Thorton) finally put in place a plan for integration, among the first in the state of Alabama to do so (and used as a model, for better or for worse). The plan that both school systems adopted in 1965 was one of “freedom of choice,” which ostensibly allowed students to choose which school within the district they wanted to attend, though schools maintained the right to deny admission based on “overcrowding.” This led to criticism on all sides—from George Wallace to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Some resisted any integration, As one SNCC Report (page 20) stated these freedom of choice plans were actually a “farce”—“How can a choice be free when often it is a choice between a students’ parents losing their jobs or transferring their child to a white school?” And yet, incremental progress towards integration began. (Associated Press, “School Integration Climbs,” Florence Times, September 7, 1966.) At least 16 black students integrated Muscle Shoals High School during the 1965-66 school year and in the Fall of 1966, students at Trenholm High School began transferring to the all-white Deshler in Tuscumbia. By the fall of 1968, Trenholm had closed. In 1969, Florence’s Burrell-Slater closed, with students largely attending Coffee High School. While this consolidation indicates progress on racial integration, it also, importantly, represents a loss of autonomous educational and communal spaces for the black community. (For more on this, see the work of Vivian Gunn Morris and Curtis L. Morris: The Price They Paid: Desegregation in an African American Community (Teacher’s College Press, 2002); and Creating and Nurturing Educational Environments for African American Children (Bergin and Garvey, 2000). For more of Vivian Gunn Morris’ work, see also this interview with NPR.

Some Figures

- In Colbert County, under the freedom of choice plan, the figures for the 1965 school year were: 4120 white students enrolled; 254 Black students enrolled; and 50 Black students enrolled in “white schools.” (The designation for this in the records is “Negroes enrolled with whites”)

- In Muscle Shoals, under the freedom of choice provisions, the figures for the 1965 school year were: 1270 white students enrolled; 216 Black students enrolled; 20 Black students enrolled in white schools; for an integration of 9.25%.

- In Sheffield, the figures for the 1965 school year were: 2468 white students enrolled; 706 Black students enrolled; 75 Black students enrolled with white students; an integration rate 10.62 %. In Sheffield, grades 1-6 integrated under the Freedom of Choice plan; grades 7-12 attended the school in their geographic zone.

- In Lauderdale County, under the freedom of choice plan, the figures for the 1965 school year were: 7416 white students enrolled; 792 Black students enrolled, 75 Black students enrolled with white students, for an integration rate of .94.

- In Florence (city), the figures under the Freedom of Choice plan were: 6154 white students enrolled; 1402, Black students enrolled; 120 Black students enrolled with white students, for an integration rate of almost 10%, among the best percentages in the state, the highest given its relative size, and the most black students enrolled by far (SNCC Report, p 53).

*(By way of comparison, take for example, Birmingham: 37861 white students, 35162 Black students, 53 Black students enrolled with white, an integration rate of .15%, under court order. The state totals for 1965-1966: 575,000 white students; 300,000 Black students; 1500 Black students enrolled with white students; an integration rate of .5%)

In the Shoals, integration meant that black students became minority members in white schools, with majority white teachers and administrators. Some celebrated this peaceful change, while others grieved it. As one prominent black writer put it: “The Supreme Court decision…didn’t give us school integration in Tuscumbia, it gave us school elimination.” (Morris, The Price they Paid, 2002)

This integration also consolidated employment for educators, often with deleterious effects for Black teachers

Desegregation was also important in terms of athletics. The year Deshler desegregated Porter Thomas joined the football team. From 1965-1968, athletic integration at the secondary level was limited to single individuals like Thomas. But when black schools began to close heading into the fall of 1968, teams integrated substantially. Eleven black players joined Deshler that season, as did Charles S. Mahorney who became an assistant coach. In 1969, thirteen black football players followed their coach, Harvest Mitchell (who coached with Joe Grant, a white coach), from Burrell-Slater to Coffee, making the football team the most integrated in the area. While integrated teams largely performed well, integration caused unintended negative consequences for black coaches, who were typically relegated to “Assistant” roles (Harvest Mitchell, Charles Mahorney, Milton Franklin). Some of them later switched to basketball to become the head coach. In at least one case, Black coaches issued lawsuits for being passed over for head coaching jobs due to racial discrimination. In March of 1972, the 5th US Circuit Court of Appeals “ordered the Florence, Ala. School Board to provide a head coaching job” to Harvest Mitchell, revealing that, despite relatively peaceful integration in athletics, discrimination endured, particularly in employment. He was granted the position, but terminated four years later. (“Court Supports Black Coach,” Florida Sentinel-Bulletin, March 14, 1972.) UNA alumnus, Brian Corrigan, conducted an oral history with Coach Harvest Mitchell with the following remarkable quote:

I grew up in south Alabama, down below Birmingham, and that is where all the noise was… all of the fighting, and all of the demonstrations, and all of that. Because I was part of it. Alabama State University was just above Dr. King’s church… I grew up in that atmosphere…. When I came to Florence, the superintendent asked me, by telephone, he said, ‘You’re not going to bring any of that stuff with you, are you?’ I looked over at my wife and my son, and I said, “No! No, I don’t think I am!” This was my first job. And sometimes, along the way in your life, you have to hide a certain element, or certain thought, until that time comes. And it will come. You will have to stand up and display it. And that was that situation.” (Interview of Mitchell by Corrigan, 2016)

Integration of Higher Education

On September 11, 1963, Wendell Wilkie Gunn became the first black to student to enroll at Florence State College (now the University of North Alabama). After requesting an application from Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Dr. Turner Allen, Gunn was sent to the President’s Office where he came to face with Dr. E.B. Norton. “After asking me several challenging questions about my motives, who sent me, and such,” Gunn recalled, “President Norton explained to me his inability, under Alabama law and the college, to accept a Negro for admission.” However, Norton then took the extraordinary measure of instructing Gunn that if he mounted a legal challenge, it would likely be successful, indicating, too that the College would comply. Retaining the counsel of famed civil rights attorney Fred Gray, Gunn took his case to federal court. The case “took all of ten minutes,” Gray remembered, as the court issued a federal order for Gunn’s immediate admission. Gunn enrolled immediately, making history. Though he faced threats, some of them violent, and isolation in his first year, Wendell Gunn excelled at Florence State, earning top grades and participating meaningfully in collegiate life. His story stands out in the litany of integration narratives as remarkably successful, long a boast of not only the college but the community. Please see the Oral History with Wendell Gunn.

And yet, the simple story of Gunn’s integration at UNA obscures a more complex reality for Florence State. The school was dependent on federal funds, with diminishing resources incoming from the state, and could scarcely risk alienating the federal government. Integration was as much an economic decision as a social one. An editorial from the week before Gunn’s enrollment is also telling. In the Flor-Ala, Norton wrote: “extreme elements, whether they be composed of segregationist or integrationist factions, have no proper place on our college campus.” In allowing for integration as quietly as possible, E.B. Norton prevented a confrontation, or even robust conversation, about education and racial equality while keeping federal money flowing into the school’s coffers.

Five years after Wendell Gunn integrated Florence State, in 1968, Bobby Joe Pride and Leonard “Rabbit” Thomas became the school’s first black athletes. For context, this was two years prior to Auburn University and three years prior to the integration of the University of Alabama’s football teams.

Racial Violence

Despite the Shoals’ reputation for being peaceable there were instances of violence. Racial violence intended to create fear and sustain a system of white supremacy had long stalked the Shoals. In the 20th century, numerous lynchings occurred. (Please see Shoals Black History) That violence continued into the civil rights era. For instance, in 1949, a Tuscumbia woman, Mrs. Mamie Patterson, a fifty four year old mother of six, was raped at gunpoint by two white men. They intruded into the home claiming they were seeking a debt repayment and beat her husband, James Patterson, into unconsciousness before assaulting her. (From the AP Press: “Mrs. MAMIE PATTERsoN, 54, of Tuscumbia, Alabama, mother of six children, was raped at pistol point by Charles Berryhill, 29, and Herschel Gasque, 27. The two men forced their way into the Patterson home, struck JAMES PATTERSON, her husband, over the head, beating him into unconsciousness. The men claimed they were trying to collect a debt from Patterson. They then raped Mrs. Patterson.”)

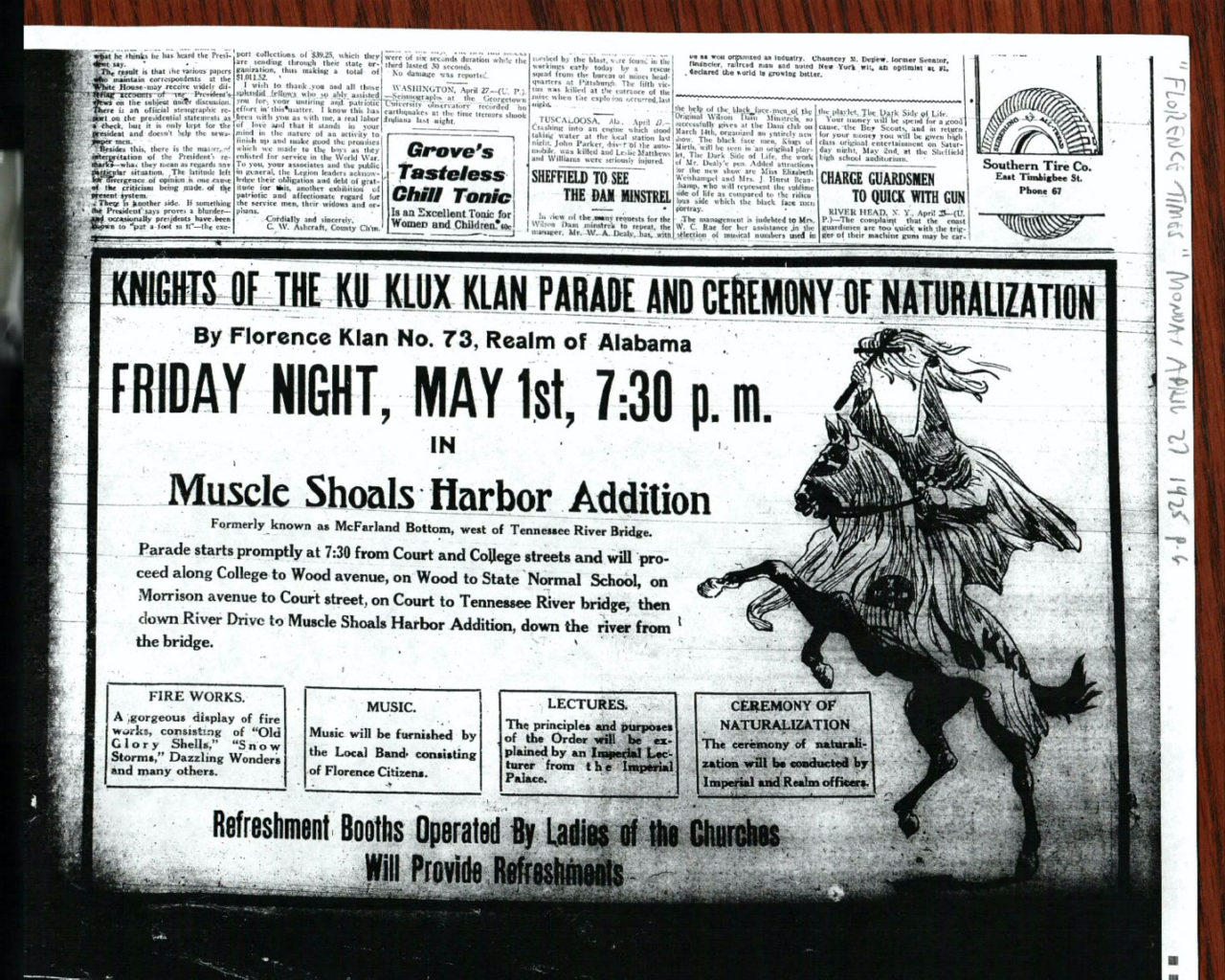

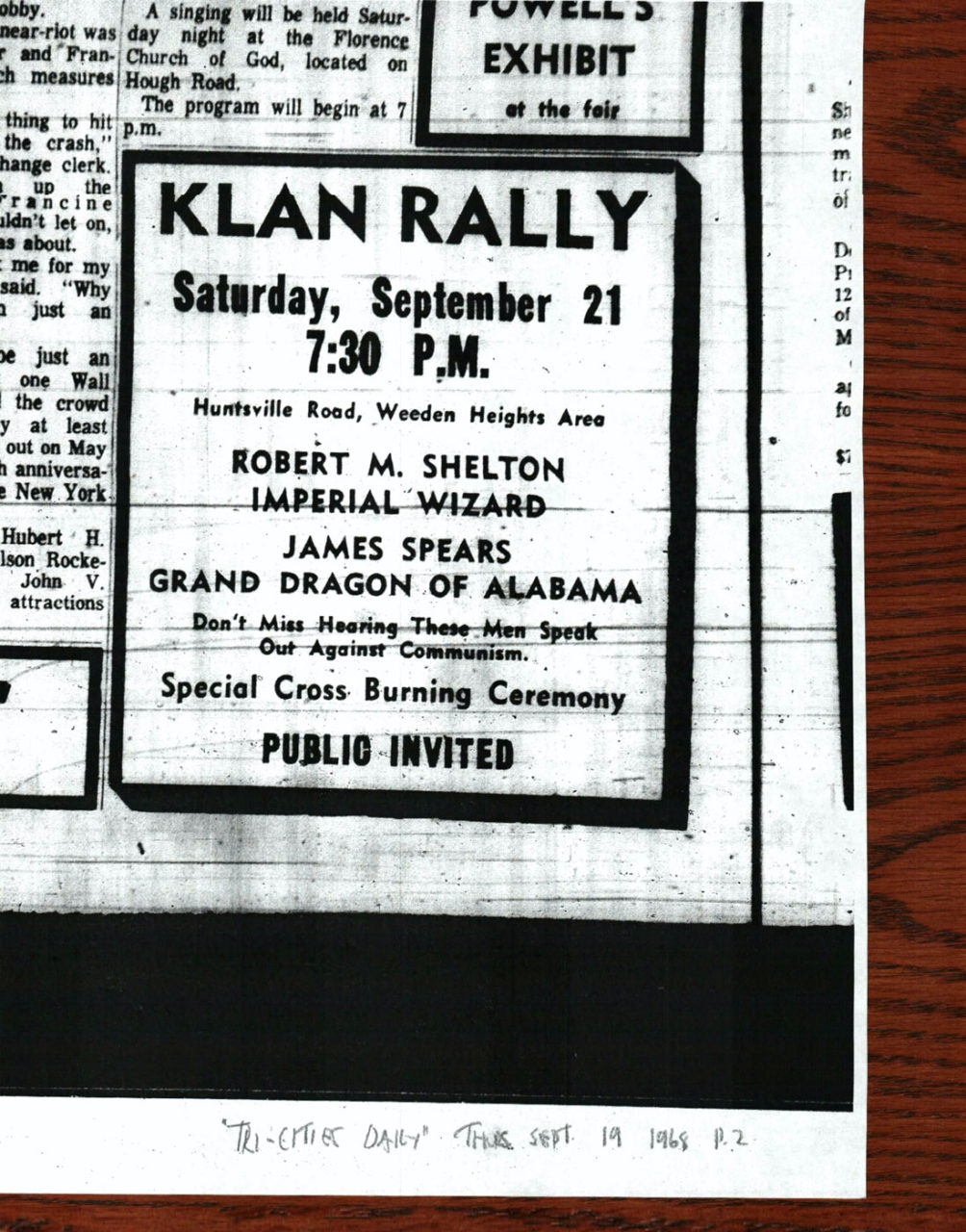

While the violence of white supremacy was, in some senses, ever present, the Shoals experienced less than other parts of the state. Anti-Civil rights organizations, like the American States Rights Association, did not have chapters here, nor, apparently, did the White Citizens Council. However, the Ku Klux Klan was active. In the early twentieth century, the Klan policed race, held parades, and met regularly. (Please see Shoals Black History). They intimidated black leaders and entrepreneurs. Some recall hooded members surrounding the black elementary school in Tuscumbia– picking up trash, but offering a menacing reminder. In 1967, the KKK held a massive rally at the Florence-Lauderdale Coliseum, where they denounced the federal government, a clear critique of federal civil rights legislation. (“Federal Bureaucracy Lashed by Klan Chief.” The Time – Tri-Cities Daily, June 11, 1967) In 1968, the Klan held another rally, advertised in the Tri Cities Daily on Sep 19, 1968, on Huntsville Road in Florence. This gathering, open to the public, boasted the Imperial Wizard, Robert Shelton and Grand Dragon of Alabama James Spears, as well as a “Special Cross Burning Ceremony.” Crosses were also burned in front of the Rosenbaum house, ostensibly due to the family’s support for racial integration.

Though the Shoals had an active Klan presence and black citizens were constantly subjected to the threat of violence, much of the tension was mollified by a biracial group of civil and religious leaders intent on preserving peace. This Interministerial Alliance met regularly, seeking peaceful cooperation based on shared religious beliefs. While some congregations actively opposed racial integration, others, like First Presbyterian Church, welcomed Black members in the 1960s without incident. For in-depth interviews regarding various Civil Rights topics in the Shoals, please see the collection of Oral Histories from the Florence-Lauderdale Public Library.